Design Web Design Web Design & Development

Essential Tips for Collaboration Between UI Designers and Front End Developers

By \ April 13, 2018

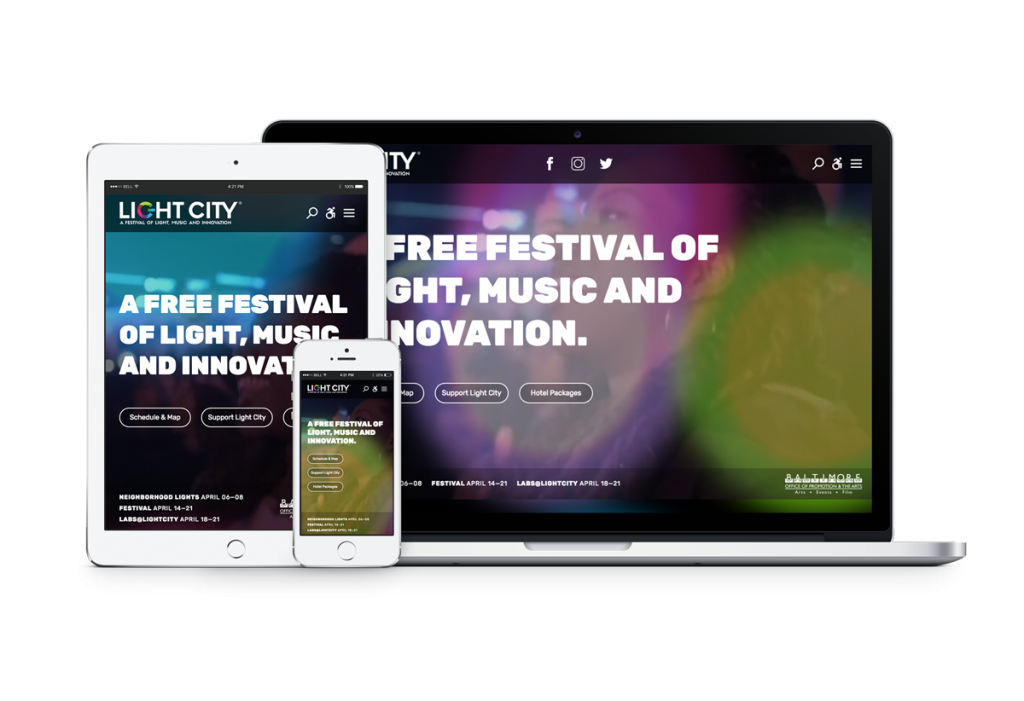

Earlier this year, we were given a challenge: Design, build, test, and deploy a brand new site for Light City in four weeks. Given the three-year old festival’s visibility and importance for Baltimore and its visitors, we knew we wanted to push ourselves to produce a high-quality experience and showcase the captivating spirit of Light City.

Reflecting on our own experiences attending the festival in previous years, reviewing photos and video clips, and listening to our friends at the Baltimore Office of Promotion and Arts describe the vision for this year’s Light City, we were inspired to create an interactive light show of our own on LightCity.org

The fast-paced and ambitious nature of the project required that we collaborate on each component as closely and efficiently as possible. We learned a lot from the experience and developed processes and skills that we carry forward.

Drawing from what we’ve learned, we’ve developed the following 20 tips (10 for designers, 10 for developers) to improve collaboration, workflows, and ultimately the final product.

20 Tips to Improve Collaboration, Workflows, & the Final Product

1) Developers: Prioritize visual hierarchy over pixel perfection.

It is more important to maintain the proportions and hierarchy between elements in a design than it is to use the exact pixel-for-pixel sizes found in a design file.

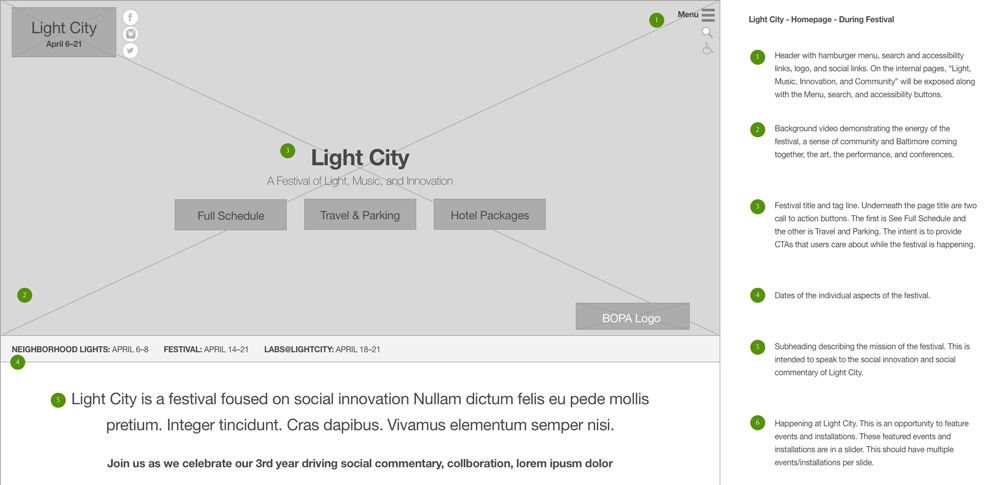

For fast-paced projects like LightCity.org, where time is precious, it isn’t the best use of a designer’s time to create numerous versions of each design to show how it scales across every possible screen size. Even without the time pressure, there are infinite resolutions for viewing websites. It is unreasonable—and impossible—to ask designers to provide flats for each.

Instead, designers can create a mobile design and a design for a widescreen desktop that establish proportions between type, images, and surrounding elements. It is then the frontend developer’s responsibility to build for those two screen sizes first, check every screen size in between, and make size adjustments that are appropriate for each screen while maintaining the established proportions.

2) Designers: Know your medium.

Designing websites requires the creation of scalable systems that can adjust to the infinite available resolutions at which a user might view a site. Not only should designers be aware of what happens to a system when it’s scaled down (e.g. for mobile and tablet), but they should also account for when a system is blown up on larger screens. Is there a max-width on elements or do things scale infinitely? Can the resolution of the the assets provided hold up to the scaling? If not, what happens beyond the edges?

3) Developers: Ask questions.

Balancing time while pushing for quality requires continuous communication between project managers, designers, and developers. A developer asking detailed questions before, while, and after producing each major component can save the time that would otherwise be wasted building a complex component before fully understanding its design or functionality. If a developer can make something that accomplishes 90% of the component’s intent in 20% of the time, that tradeoff is often beneficial for everyone.

On occasion, designers can overlook a button’s hover state or what a menu looks like when it’s toggled open. Frontend developers should understand the intent of the component and the rest of the design well enough to execute on inferences about the design. These smaller design decisions can be reviewed with the rest of the team after the fact, but for more complex components it’s important to get guidance first.

4) Designers: Know your developer.

If you are fortunate enough to know which developer you will be working with on a project, it is helpful to involve them as early in the design process as possible. This allows for the opportunity to check in with them regularly about whether or not what is being envisioned is possible within the developer’s pace and skill set in the given timeline.

5) Developers: Contribute.

Designers are the experts in what looks right and works in the intended manner for a project, but developers are the experts in what can actually be executed. Developers should strive to realize the designer’s vision as closely as possible while explaining tradeoffs and limitations of various approaches.

If a developer can’t make exactly what they’ve been asked to make in the time they’ve been given, how close can they get by making modifications? Do those modifications still meet the design goals of the project?

6) Designers: Collaborate during frontend development.

Designers at idfive have honed their UI design skills by working directly with frontend developers while they build out designs. Collaborating early and often saves time in the final quality control process as there are fewer design-related issues to fix. Just working in close proximity, even if a designer is actively working on another project while the developer builds their design, makes the designer available for quick questions and problem solving that may otherwise require a formal meeting to address.

7) Developers: Understand first.

Developers should have an intimate understanding of the design, its audience, its intention, and at least a rough outline of implementation details before writing any code. This understanding allows for planning, componentization, and efficiency as they can produce more code without needing to stop as frequently to ask for clarification. If a module is used on a homepage, can it be reused on an internal page with some configuration tweaks? The more complete a developer’s understating from the start, the better they can answer these questions.

8) Designers: Patterns are your friend.

Just as patterns in design reduce friction for users trying to understand your site, they also reduce friction for the developers trying to build it. The more patterns you use, the more developers can reuse code, and the more time they have to build your amazing complex homepage animations, etc.

9) Developers: Be your own quality control.

Not receiving a design for something in a design-dev handoff isn’t an excuse for it to look bad in production. We all make mistakes. We all overlook things. We can be doing our absolute best job and still forget to ask for (or on the design side, forget to create) a design for what a menu looks like when it’s opened, or a design for a hover state. That doesn’t mean we can just make something gross (or not make it at all) and call it a day. If you can make something simple that looks good quickly, do that and ask if it’s ok. If you need guidance from a designer first, let them know right away, and find a solution. It shouldn’t need to be found in QC if you know it’s not up to par.

10) Designers: Document it.

If you’re designing interactions and animations, document and explain your designs. If possible, create animated samples. Have answers to common questions from developers before they need to ask.

11) Developers: Keep your knowledge of new and existing technologies up-to-date.

This means understanding what is hot and new and widely-supported in modern browsers, but it also means knowing that while it may have been cool in 1995, it is no longer cool to put non-tabular data in a table for layout. Designers can look around the web and see other developers pulling off cutting-edge designs that require new tools and skills. Learn them.

12) Designers: Learn about browsers and what they can handle.

Will an interaction or animation cause performance degradation for users? What can you cut back while maintaining quality? No one will care that your site looks good if it’s too slow to be used.

13) Developers: Use the right tools.

Lots of UI elements can be built to look and behave the same using a variety of different technologies. It’s important to know which tools to select for each circumstance. Do you use an SVG or build the icon with HTML and CSS? SVGs are great and scalable and can let you insert complex shapes, but they have some quirks that can make them difficult to style. Sometimes simple HTML and CSS elements and pseudos will be more flexible and easier to style. Do you need a Javascript library or WordPress plugin or can you make something more efficiently from scratch?

14) Designers: Use developers as resources.

If you’re struggling with a particular design choice early in a project, your dev might have an idea or solution that will save you the time and frustration of re-inventing.

15) Developers: Consider everyone.

Think about wide use cases — how does your site perform when network connectivity is poor? Are the tap targets large enough for the average person to use comfortably? Think about blind and low vision people, people with motor disabilities, and site users who may speak a different language. You can’t necessarily accommodate every single consideration, but you should at least be aware of best practices.

16) Designers: Consider logic from the start.

What determines an element’s size? Is it fixed or flexible? Where is each feed of information coming from? How is it ordered and prioritized? Why? What about on smaller screens with less space?

17) Developers: Plan ahead and don’t do things twice.

We’ve all heard “don’t repeat yourself” (DRY) as a programming best practice, but it extends beyond reusable classes and functions. If you get a 12MB image, don’t let it touch your repo if you’re just going to have to go back and swap it out for an optimized version later. Use a placeholder or get optimized assets first. Don’t assume that a four-photo carousel will always have four photos. Have a plan for if you’re asked to change it to five at the last minute.

18) Designers: Be prepared for a thorough handoff.

Whenever you’re preparing for a design-dev project handoff, make sure you have fonts, colors, and images organized in a way that makes it easy for developers to plug them in and move on. This gives them more time to concentrate on executing your design. Optimize image files early (with something like tinypng.com) so you aren’t spending time in quality control finding and replacing huge files that never should’ve made it into the project in the first place.

19) Developers: Defend your work.

There’s a common misconception that building an accessible website means giving every image a descriptive alt attribute. In fact, giving a descriptive alt attribute to non-vital page content (like a background image that’s part of the design, but not really part of the content) is unnecessary and can be distracting. Those images should have ‘alt=“”’. If you’re asked to add them, know why that’s the wrong approach, and push back. If you’re asked to put text in an image or video that makes more sense to be rendered as actual page text, explain why and advocate for your approach.

20) Designers: Be an advocate for your developer.

Learn about what your developer is interested in building and see if you can find a way to incorporate that into your designs. You’re more likely to get good results if both of you are invested in making it look and work a certain way.

More Learning to Come

We hope these tips will help make it easier for dev-designer duos out there to work together more efficiently, and tackle ambitious projects in the future.

As we sharpen our own skills (we still have so much to learn!) and get more comfortable and familiar with each other’s abilities and priorities, we’ll continue to share what we learn with you, too.

The adventure continues.